GSMI & Keeper: Why They’re Warren Buffett-Type Stock Picks

To understand what a Warren Buffett–style stock pick is, let’s look at Isaac Asimov’s classic science fiction series Foundation. In the books, a character named Hari Seldon develops a field called psychohistory - a blend of math, statistics, and sociology designed to predict the future.

The main idea is simple: you can’t predict what a single person will do, but you can predict the general patterns of large groups. Seldon was able to use this concept to accurately forecast multiple events far into the future.

Think about that for a moment. The collective behaviors of large groups create predictable patterns. And because those patterns are reliable, they can be used to predict what the future might look like.

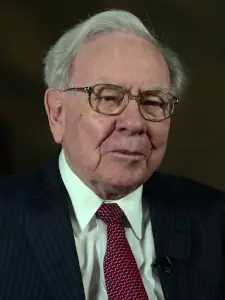

And everybody acknowledges that Warren is the master of buying stocks with a predictable future. He often shares in interviews that predictability is the investor’s friend. If something is hard to predict, it’s hard to make informed decisions. That’s why focusing on predictable businesses is the smart move.

But the big question is this: how does he actually identify and predict which stocks, businesses, and future growth are worth betting on?

This is where most people fail when they try to replicate Buffett. They look at a company’s financial history and try to project it forward. If revenues and income are growing at a steady pace, investors assume the momentum will just keep going.

But there’s a big hole in that assumption: financial performance is the output, not the input. That’s why the timeless wisdom holds true - past performance does not guarantee future results.

So if financial results are just the output, then what really drives them? What’s the actual input that creates those numbers - the thing Buffett pays attention to long before the revenues and profits show up on a financial statement?

The actual input is simple: Consumer behavior and habits.

One of the best examples is Buffett’s massive holding in Coca-Cola, which has brought him tremendous wealth over the years. The concept is simple: people are hooked on Coke products, and the habit of drinking them has built unstoppable momentum for more than a century. That momentum hasn’t slowed down - generation after generation keeps drinking Coke, and that’s the input driving Coca-Cola’s steady revenue growth.

What’s remarkable is how resilient this behavior has been. It has stood the test of time, unaffected by technology shifts like the internet, mobile phones, or even artificial intelligence. And it hasn’t been shaken by world events either - not by political conflicts, economic downturns, inflation, recessions, wars, or even global pandemics. The demand has remained consistent, and the growth continues.

This is the core of Buffett’s genius: identifying businesses where consumer behavior and habits serve as reliable inputs, pushing revenues and profits far into the future with a high degree of predictability.

And that brings us to our main topic: GSMI and KEEPR - which I believe are even stronger bets than Coca-Cola. Why?

Coca-Cola has been around for more than a century. But the core business of GSMI and KEEPR - alcoholic beverages - has been around for thousands of years. From the earliest recorded history, people have always been drinking.

Now, if you survey almost anywhere in the Philippines - from busy city corners to the most remote rural provinces - two drinks consistently stand out: gin and related products from GSMI, and Alfonso from KEEPR. These are among the most popular alcoholic drinks in the country. This is what people drink. For the hardworking men and women who look forward to going merry with friends every weekend, these brands are their consistent choice. They command the most massive volume in the country today.

Imagine the power of that habit: the expectation of hardworking Filipinos, used to the familiar taste, looking forward to GSMI Gin and Alfonso every single weekend.

These habits are not new. I’m close to five decades old, and since childhood I’ve seen people in my neighborhood drinking GSMI gin - that’s decades of habit. Yes, Alfonso is a bit newer, but it is now close to three decades old, slowly building its base of drinkers and gaining momentum over the years. These two brands are the top choice for taste and price balance.

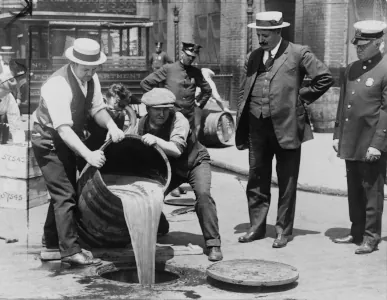

But you might ask, will an extreme event ever disrupt this drinking habit? There is always a chance, but history teaches us that it is highly unlikely.

Consider the Prohibition Era in the United States, which banned liquor for many years. Did it stop the masses from drinking? No. History tells us drinking did not stop; only the dynamics of who supplied it, and how and where they supplied it, changed. The consumer habit never died.

Even here in the Philippines, under President Duterte - a leader feared for his strict policies. When he banned drugs, people got scared. When he banned firecrackers, people followed. But when he announced a liquor ban during the 2020 pandemic, no one really stopped. If you check the financials of GSMI and KEEPR, 2020 was still a strong year. Sales held up, proving just how hard it is to break this consumer habit.

At the end of the day, this is what Warren Buffett has been teaching all along. It’s not about projecting or extrapolating financial results - it’s about understanding the habits and behaviors that drive revenues in the first place. Coca-Cola was his bet on an unshakable habit.

Here in the Philippines, GSMI and KEEPR stand on the same foundation - businesses rooted in consumer behavior that has stood the test of time. Drinking is a habit so deeply ingrained that it is unlikely to be disrupted by any new technology or even major global events. Consumers will always find ways to keep it going, and that makes the business highly predictable. And as Buffett says, predictability is the investor’s friend.

That’s what makes them Buffett-type picks: companies where the future is predictable, not because of past numbers alone, but because of the timeless human behaviors that keep driving those numbers forward.